From former Labor Secretary Robert Reich writing in the NYT:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/04/opinion/sunday/jobs-will-follow-a-strengthening-of-the-middle-class.html?_r=2&pagewanted=1

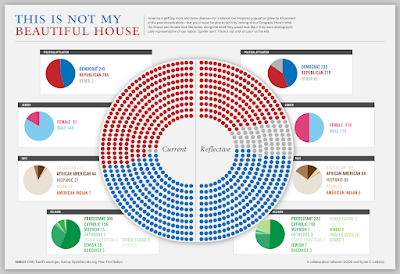

The graphic says it all -- and I do mean all!

http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2011/09/04/opinion/04reich-graphic.html?ref=sunday

The purpose of this blog is to serve as a quick reference to political and economic data presented primarily in graphical format, with tables and other charts where appropriate. Use the search box to quickly locate the data you are seeking. Go Dems!

Monday, September 5, 2011

Excellent Link from Jared Bernstein's Recent Blog Post

Jared linked to this from Citizens for Tax Justice web site -- you should download the PDF from the CTJ site:

Recent data show that the U.S. is taxed far less than almost all other OECD countries. An increase in revenue is the obvious answer to America's budget deficit.

http://www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/06/us_one_of_the_least_taxed_developed_countries.php

Recent data show that the U.S. is taxed far less than almost all other OECD countries. An increase in revenue is the obvious answer to America's budget deficit.

http://www.ctj.org/ctjreports/2011/06/us_one_of_the_least_taxed_developed_countries.php

Saturday, September 3, 2011

CBO: Up to 2.9 Million People Owe Their Jobs to the Recovery Act

Jon Stewart Daily Show August 18 2011 Episode

Great Jon Stewart segment on income inequality -- watch the first 5 minutes:

http://www.thedailyshow.com/full-episodes/thu-august-18-2011-anne-hathaway

Here is a link to the data from the CIA factbook -- note that this is sorted 'worst to best' whereas the Jon Stewart table sorts from 'best to worst.'

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html

http://www.thedailyshow.com/full-episodes/thu-august-18-2011-anne-hathaway

Here is a link to the data from the CIA factbook -- note that this is sorted 'worst to best' whereas the Jon Stewart table sorts from 'best to worst.'

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html

More about Who Pays Taxes

Fiscal Times weighs in on the fashionable Republican rant about tax rates for the poor:

http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2011/08/31/Who-Pays-No-Taxes-and-Why-Theyre-No-Pot-of-Gold.aspx#page1

Can you believe the argument advanced by theKoch er, Cato Institute senior fellow? (sarcasm filter on) Yes, let's go out of our way to withdraw benefits from the lower income 50% of American citizens who control a whopping 2.5% of US wealth!! (sarcasm filter off)

http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2011/08/31/Who-Pays-No-Taxes-and-Why-Theyre-No-Pot-of-Gold.aspx#page1

“It’s wrong to rail on the 46 percent of people who don't pay income tax,” said Paul Caron, a tax professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Law. “A fairer analysis takes into account all taxes paid—and by this measure, everyone has tax skin in the game,” he said.

It will be hard to change or eliminate the social policy-related tax provisions that knock millions of Americans off the federal income tax rolls, said Roberton Williams, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center. Not only would it risk alienating key voting blocs, such as senior citizens, but it could have a serious economic impact, he said. “It’s going to hurt the economy more if you raise taxes on the poor than the rich, because the poor spend every penny they’ve got,” Williams said. “If you take a dollar away from them in tax credits, that’s a dollar they don’t spend.”

Not everyone considers these tax breaks untouchable, however. “This proliferation of credits and benefits at the bottom has really gone too far,” said Chris Edwards, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute. “There are all kinds of pro-market policies the government can do to offset any harm caused to these people if it’s going to withdraw benefits,” he said. Repealing tariffs on goods from China and other countries would lower the cost of clothing and food for low-income Americans to balance the absence of tax credits, he said.

Can you believe the argument advanced by the

Friday, September 2, 2011

Rick Perry By the Book

From WaPo columnist Ruth Marcus:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/rick-perry-by-the-book/2011/08/30/gIQAJJsbqJ_story.html?hpid=z2

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/rick-perry-by-the-book/2011/08/30/gIQAJJsbqJ_story.html?hpid=z2

"Perry’s 2010 Tea Party-steeped manifesto, “Fed Up!,” makes George Bush look like George McGovern. Perry has said he wasn’t planning to run for president when he wrote the book, and it shows."

The ratio of corporate profits to wages is now higher than at any time since just before the Great Depression

http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2011/sep/01/robert-reich/robert-reich-says-ratio-corporate-profits-wages-hi/

From the site:

In an Aug. 29, 2011, column, Robert Reich, the former Labor Secretary under President Bill Clinton and a frequent liberal commentator, offered a number of statistics to back up his call for worker protests rather than parades on Labor Day.

"Labor Day is traditionally a time for picnics and parades," Reich’s column began. "But this year is no picnic for American workers, and a protest march would be more appropriate than a parade."

One of the statistics Reich offered was this: "The ratio of corporate profits to wages is now higher than at any time since just before the Great Depression."

A reader asked us to check this out, so we did.

We turned to statistics compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the federal office that calculates official statistics about the economy. We found numbers for corporate profits as well as for two measures of worker income -- wage and salary disbursements, and total employee compensation received. We then divided corporate profits by both of the income measurements, all the way back to 1929. (Here are the full statistics from 1929 to 2011 as we calculated them.)

For wages, we found that Reich was essentially correct. The ratio in 2010 -- the last full year in the statistics -- was .281, which was higher than any year back to at least 1929, the earliest year in the BEA database. The next highest ratio was in 2006, at .265. (We didn’t find pre-1929 data, so the one part of Reich’s statement that we can’t prove is that the ratio was higher "just before the Great Depression.")

We also looked at total compensation, since the portion of worker compensation delivered outside of wages has grown significantly since 1929. The numbers were slightly different, but the general pattern still held. The ratio in 2010 was .226, which was matched or exceeded in only four years -- 1941, 1942, 1943 and 1950.

To capture the most up-to-date trends, we also looked at the ratios for the last six quarters. For both wages and compensation, the ratio has risen steadily over that year-and-a-half period. For wages, the ratio has climbed from .274 in the first quarter of 2010 to .290 in the second quarter of 2011. For compensation, the ratio has risen from .220 in the first quarter of 2010 to .234 in the second quarter of 2011.

So numerically, there’s little question that Reich is essentially right. (Or, at least for now he is. Economists note that statistics about corporate profits and wages are often revised after the fact.) A more interesting question is what this trendline actually means.

First, we’ll note that the ratio has been remarkably steady over the time we studied. In 2010, corporate income was 168 times what it was in 1929, and wages were 124 times what they were in 1929. But despite the dramatic increases for both measures individually, these two numbers have grown pretty much in tandem. While corporate profits have grown faster, they haven’t grown dramatically faster. Over the eight-decade period, the ratio between corporate profits and wages -- at least prior to 2010 -- almost always hovered between .150 and .235, a pretty narrow range, all things considered.

Within this range, the ratio has regularly zigzagged up and down. The ratio has peaked during World War II, the early 1950s, the mid1960s, the mid1990s and the middle of the first decade of the 21st century.

The 2010 high broke with this history, making the statistic Reich is talking about all the more striking. And as the quarterly data shows, the spike from 2010 has continued into 2011.

This spike has its roots in basic mathematics. The ratio can rise for either of two reasons -- because corporate profits rise, or because wages stagnate. To a greater degree than in past recessions, both of these developments have happened simultaneously in 2010 and 2011. That’s the immediate reason for the ratio’s sudden increase. The ratio was well within historical norms as recently as 2009, the second year of the recession.

Today, "indicators favorable to workers are either absolutely dreadful, like the percentage of the adult population that is employed, or else improving at a not-very-robust rate, like real compensation per hour, while indicators favorable to business owners, such as record profit levels measured in billions of current dollars, are very delightful indeed," said Gary Burtless, an economist at the centrist-to-liberal Brookings Institution.

There are any number of explanations for why businesses are so reluctant to invest their profits today. For instance, Dan Mitchell, an economist at the libertarian Cato Institute, said the pattern of low corporate investment that we’re seeing today has to do with "a climate of economic uncertainty, largely thanks to the threat of more taxes and regulations."

But the explanation that seems to mesh best with our numbers has to do with economic cycles. While the ratio Reich points to is exaggerated today due to an unusually deep recession and an especially sluggish recovery, the general pattern follows that of other recent recessions, said J.D. Foster, an economist with the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Typically, businesses initially lose ground during a recession, while workers suffer somewhat less, in part due to "sticky wages" -- the tendency for worker pay to increase or stagnate rather than fall, even in hard times. This pattern tends to decrease the ratio of corporate profits to wages.

However, when the recovery begins, the reverse becomes true -- businesses tend to gain ground faster than workers do, since soft labor markets prevent workers from reaping the rewards of improved productivity. This pushes the ratio of profits to wages higher. Since the current recovery is particularly weak, the increase in the ratio has been even stronger than normal.

The hopeful news for workers, Foster says, is that once a recovery gathers steam and new capital-labor equilibrium is reached, workers tend to accelerate their gains.

"Once a strong recovery is under way and labor markets return to normal, total labor compensation tends to catch up, as employers bid for employees out of the extra profit margin they accumulated during the recovery," Foster said. "So once we start heading toward full employment, we can expect total labor compensation to rise very rapidly relative to total income."

So where does this leave us? On the numbers, Reich’s claim is essentially correct. And in his analysis, Reich doesn’t over-promise on what the data indicate. Amid evidence that these numbers could turn out to be a temporary spike, he resists the temptation to label it the culmination of a long-term trend. We find Reich’s formulation both factually supportable and appropriately cautious in its interpretation. We give it a rating of True.

From the site:

In an Aug. 29, 2011, column, Robert Reich, the former Labor Secretary under President Bill Clinton and a frequent liberal commentator, offered a number of statistics to back up his call for worker protests rather than parades on Labor Day.

"Labor Day is traditionally a time for picnics and parades," Reich’s column began. "But this year is no picnic for American workers, and a protest march would be more appropriate than a parade."

One of the statistics Reich offered was this: "The ratio of corporate profits to wages is now higher than at any time since just before the Great Depression."

A reader asked us to check this out, so we did.

We turned to statistics compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the federal office that calculates official statistics about the economy. We found numbers for corporate profits as well as for two measures of worker income -- wage and salary disbursements, and total employee compensation received. We then divided corporate profits by both of the income measurements, all the way back to 1929. (Here are the full statistics from 1929 to 2011 as we calculated them.)

For wages, we found that Reich was essentially correct. The ratio in 2010 -- the last full year in the statistics -- was .281, which was higher than any year back to at least 1929, the earliest year in the BEA database. The next highest ratio was in 2006, at .265. (We didn’t find pre-1929 data, so the one part of Reich’s statement that we can’t prove is that the ratio was higher "just before the Great Depression.")

We also looked at total compensation, since the portion of worker compensation delivered outside of wages has grown significantly since 1929. The numbers were slightly different, but the general pattern still held. The ratio in 2010 was .226, which was matched or exceeded in only four years -- 1941, 1942, 1943 and 1950.

To capture the most up-to-date trends, we also looked at the ratios for the last six quarters. For both wages and compensation, the ratio has risen steadily over that year-and-a-half period. For wages, the ratio has climbed from .274 in the first quarter of 2010 to .290 in the second quarter of 2011. For compensation, the ratio has risen from .220 in the first quarter of 2010 to .234 in the second quarter of 2011.

So numerically, there’s little question that Reich is essentially right. (Or, at least for now he is. Economists note that statistics about corporate profits and wages are often revised after the fact.) A more interesting question is what this trendline actually means.

First, we’ll note that the ratio has been remarkably steady over the time we studied. In 2010, corporate income was 168 times what it was in 1929, and wages were 124 times what they were in 1929. But despite the dramatic increases for both measures individually, these two numbers have grown pretty much in tandem. While corporate profits have grown faster, they haven’t grown dramatically faster. Over the eight-decade period, the ratio between corporate profits and wages -- at least prior to 2010 -- almost always hovered between .150 and .235, a pretty narrow range, all things considered.

Within this range, the ratio has regularly zigzagged up and down. The ratio has peaked during World War II, the early 1950s, the mid1960s, the mid1990s and the middle of the first decade of the 21st century.

The 2010 high broke with this history, making the statistic Reich is talking about all the more striking. And as the quarterly data shows, the spike from 2010 has continued into 2011.

This spike has its roots in basic mathematics. The ratio can rise for either of two reasons -- because corporate profits rise, or because wages stagnate. To a greater degree than in past recessions, both of these developments have happened simultaneously in 2010 and 2011. That’s the immediate reason for the ratio’s sudden increase. The ratio was well within historical norms as recently as 2009, the second year of the recession.

Today, "indicators favorable to workers are either absolutely dreadful, like the percentage of the adult population that is employed, or else improving at a not-very-robust rate, like real compensation per hour, while indicators favorable to business owners, such as record profit levels measured in billions of current dollars, are very delightful indeed," said Gary Burtless, an economist at the centrist-to-liberal Brookings Institution.

There are any number of explanations for why businesses are so reluctant to invest their profits today. For instance, Dan Mitchell, an economist at the libertarian Cato Institute, said the pattern of low corporate investment that we’re seeing today has to do with "a climate of economic uncertainty, largely thanks to the threat of more taxes and regulations."

But the explanation that seems to mesh best with our numbers has to do with economic cycles. While the ratio Reich points to is exaggerated today due to an unusually deep recession and an especially sluggish recovery, the general pattern follows that of other recent recessions, said J.D. Foster, an economist with the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Typically, businesses initially lose ground during a recession, while workers suffer somewhat less, in part due to "sticky wages" -- the tendency for worker pay to increase or stagnate rather than fall, even in hard times. This pattern tends to decrease the ratio of corporate profits to wages.

However, when the recovery begins, the reverse becomes true -- businesses tend to gain ground faster than workers do, since soft labor markets prevent workers from reaping the rewards of improved productivity. This pushes the ratio of profits to wages higher. Since the current recovery is particularly weak, the increase in the ratio has been even stronger than normal.

The hopeful news for workers, Foster says, is that once a recovery gathers steam and new capital-labor equilibrium is reached, workers tend to accelerate their gains.

"Once a strong recovery is under way and labor markets return to normal, total labor compensation tends to catch up, as employers bid for employees out of the extra profit margin they accumulated during the recovery," Foster said. "So once we start heading toward full employment, we can expect total labor compensation to rise very rapidly relative to total income."

So where does this leave us? On the numbers, Reich’s claim is essentially correct. And in his analysis, Reich doesn’t over-promise on what the data indicate. Amid evidence that these numbers could turn out to be a temporary spike, he resists the temptation to label it the culmination of a long-term trend. We find Reich’s formulation both factually supportable and appropriately cautious in its interpretation. We give it a rating of True.

25 CEOs Paid More Than Companies Paid in Taxes

http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2011/08/31/CEOs-Whose-Pay-Is-Higher-Than-Their-Companys-Taxes.aspx#page1

"One-fourth of the 100 highest-paid CEOs in America took home more in pay than their companies paid in taxes to the federal government, a new report says."

GOP Targets Regulatory Burdens

What about that tired cliche from the GOP about regulatory burdens being lifted to "empower the private sector"....it's a dubious claim...as the WSJ survey says, the "lack of jobs is due mainly to a lack of sales"...here's info on that:

http://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/npr/140115604/in-jobs-debate-gop-targets-regulatory-burdens

http://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/npr/140115604/in-jobs-debate-gop-targets-regulatory-burdens

Yet in a survey last month of 250 economists by the National Association for Business Economics, 4 out of 5 agreed that the current regulatory environment for American businesses was, in fact, good. In a July survey done by the Wall Street Journal in July, two-thirds of economists said the lack of jobs is due mainly to a lack of sales.

Paul Ashworth, the chief U.S. economist for Capital Economics in Toronto, was one of those surveyed.

"The weakness of the recovery, not just in consumption but across the whole economy — across whole areas of spending — is a big problem," he says. "And that's probably the key reason why firms are reluctant to be more aggressive in hiring workers."

Ashworth, who's considered one of the best forecasters of the U.S. economy, says he doubts rolling back regulations would lead to any dramatic turnaround in hiring. But that does not mean House Republicans won't try.

All Americans Pay Taxes

Link to above graph: http://www.ctj.org/pdf/taxday2010.pdf

Also see data here: http://www.responsibletaxes.org/resources/all-americans-pay-taxes/

Are We Nearing Peak Corporate Profits

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2011/09/corporate-profits/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+TheBigPicture+%28The+Big+Picture%29

Peak corporate profits should lead, under normal circumstances, to more hiring and Capex spending. However, we are not seeing enough of either.

Will the corporate version of the Paradox of Thrift become a self-fulfilling prophesy?

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Did the Stimulus Work?

Excellent study by Dylan Matthews...not only of the subject at hand but in general terms it illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of economic analyses...

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/did-the-stimulus-work-a-review-of-the-nine-best-studies-on-the-subject/2011/08/16/gIQAThbibJ_blog.html#conleydupor

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/did-the-stimulus-work-a-review-of-the-nine-best-studies-on-the-subject/2011/08/16/gIQAThbibJ_blog.html#conleydupor

Saturday, August 27, 2011

It's the Household Debt Stupid

Excellent post from Ezra Klein:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/its-the-household-debt-stupid/2011/08/12/gIQApqWcZJ_blog.html?wprss=ezra-klein

Ken Rogoff wants to call our economic malaise “the Great Contraction.” Richard Posner wants us to at least call it “a depression.” I tend to dismiss arguments over semantics, but in this case, I agree. If it were up to me, we would call what we’re in a “household-debt crisis,” or something more elegant that gets the same idea across, as that would at least help us think more clearly about what we need to do to get out. If you take the Rogoff/Reinhart thesis seriously -- and people should, and increasingly are -- what distinguishes crises like this one from typical recessions is household debt. When the financial markets collapsed, household debt was nearly 100 percent of GDP. It’s now down to 90 percent. In 1982, which was the last time we had a big recession, the household-debt-to-GDP ratio was about 45 percent. That means that in this crisis, indebted households can’t spend, which means businesses can’t spend, which means that unless government steps into the breach in a massive way or until households work through their debt burden, we can’t recover. In the 1982 recession, households could spend, and so when the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates and made spending attractive, we accelerated out of the recession. The utility of calling this downturn a “household-debt crisis” is it tells you where to put your focus: you either need to make consumers better able to pay their debts, which you can do through conventional stimulus policy like tax cuts and jobs programs, or you need to make their debts smaller so they’re better able to pay them, which you can do by forgiving some of their debt through policies like cramdown or eroding the value of their debt by increasing inflation. I’ve heard various economist make various smart points about why we should prefer one approach or the other, and it also happens to be the case that the two policies support each other and so we don’t actually need to choose between them. All of these solutions, of course, have drawbacks: if you put the government deeper into debt in order to help households now, you increase the risk of a public-debt crisis later. That’s why it’s wise to pair further short-term stimulus with a large amount of long-term deficit reduction. If you force banks to swallow losses or face inflation now, you need to worry about whether they’ll be able to keep lending at a pace that will support recovery over the next few years. But as we’re seeing, not doing enough isn’t a safe strategy, either.

Friday, August 26, 2011

Crashing the Tea Party

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/17/opinion/crashing-the-tea-party.html

GIVEN how much sway the Tea Party has among Republicans in Congress and those seeking the Republican presidential nomination, one might think the Tea Party is redefining mainstream American politics.

But in fact the Tea Party is increasingly swimming against the tide of public opinion: among most Americans, even before the furor over the debt limit, its brand was becoming toxic. To embrace the Tea Party carries great political risk for Republicans, but perhaps not for the reason you might think.

Polls show that disapproval of the Tea Party is climbing. In April 2010, a New York Times/CBS News survey found that 18 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of it, 21 percent had a favorable opinion and 46 percent had not heard enough. Now, 14 months later, Tea Party supporters have slipped to 20 percent, while their opponents have more than doubled, to 40 percent.

Of course, politicians of all stripes are not faring well among the public these days. But in data we have recently collected, the Tea Party ranks lower than any of the 23 other groups we asked about — lower than both Republicans and Democrats. It is even less popular than much maligned groups like “atheists” and “Muslims.” Interestingly, one group that approaches it in unpopularity is the Christian Right.

The strange thing is that over the last five years, Americans have moved in an economically conservative direction: they are more likely to favor smaller government, to oppose redistribution of income and to favor private charities over government to aid the poor. While none of these opinions are held by a majority of Americans, the trends would seem to favor the Tea Party. So why are its negatives so high? To find out, we need to examine what kinds of people actually support it.

Beginning in 2006 we interviewed a representative sample of 3,000 Americans as part of our continuing research into national political attitudes, and we returned to interview many of the same people again this summer. As a result, we can look at what people told us, long before there was a Tea Party, to predict who would become a Tea Party supporter five years later. We can also account for multiple influences simultaneously — isolating the impact of one factor while holding others constant.

Our analysis casts doubt on the Tea Party’s “origin story.” Early on, Tea Partiers were often described as nonpartisan political neophytes. Actually, the Tea Party’s supporters today were highly partisan Republicans long before the Tea Party was born, and were more likely than others to have contacted government officials. In fact, past Republican affiliation is the single strongest predictor of Tea Party support today.

What’s more, contrary to some accounts, the Tea Party is not a creature of the Great Recession. Many Americans have suffered in the last four years, but they are no more likely than anyone else to support the Tea Party. And while the public image of the Tea Party focuses on a desire to shrink government, concern over big government is hardly the only or even the most important predictor of Tea Party support among voters.

So what do Tea Partiers have in common? They are overwhelmingly white, but even compared to other white Republicans, they had a low regard for immigrants and blacks long before Barack Obama was president, and they still do.

More important, they were disproportionately social conservatives in 2006 — opposing abortion, for example — and still are today. Next to being a Republican, the strongest predictor of being a Tea Party supporter today was a desire, back in 2006, to see religion play a prominent role in politics. And Tea Partiers continue to hold these views: they seek “deeply religious” elected officials, approve of religious leaders’ engaging in politics and want religion brought into political debates. The Tea Party’s generals may say their overriding concern is a smaller government, but not their rank and file, who are more concerned about putting God in government.

This inclination among the Tea Party faithful to mix religion and politics explains their support for Representative Michele Bachmann of Minnesota and Gov. Rick Perry of Texas. Their appeal to Tea Partiers lies less in what they say about the budget or taxes, and more in their overt use of religious language and imagery, including Mrs. Bachmann’s lengthy prayers at campaign stops and Mr. Perry’s prayer rally in Houston.

Yet it is precisely this infusion of religion into politics that most Americans increasingly oppose. While over the last five years Americans have become slightly more conservative economically, they have swung even further in opposition to mingling religion and politics. It thus makes sense that the Tea Party ranks alongside the Christian Right in unpopularity.

On everything but the size of government, Tea Party supporters are increasingly out of step with most Americans, even many Republicans. Indeed, at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum, today’s Tea Party parallels the anti-Vietnam War movement which rallied behind George S. McGovern in 1972. The McGovernite activists brought energy, but also stridency, to the Democratic Party — repelling moderate voters and damaging the Democratic brand for a generation. By embracing the Tea Party, Republicans risk repeating history.

David E. Campbell, an associate professor of political science at Notre Dame, and Robert D. Putnam, a professor of public policy at Harvard, are the authors of “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us.”

GIVEN how much sway the Tea Party has among Republicans in Congress and those seeking the Republican presidential nomination, one might think the Tea Party is redefining mainstream American politics.

But in fact the Tea Party is increasingly swimming against the tide of public opinion: among most Americans, even before the furor over the debt limit, its brand was becoming toxic. To embrace the Tea Party carries great political risk for Republicans, but perhaps not for the reason you might think.

Polls show that disapproval of the Tea Party is climbing. In April 2010, a New York Times/CBS News survey found that 18 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of it, 21 percent had a favorable opinion and 46 percent had not heard enough. Now, 14 months later, Tea Party supporters have slipped to 20 percent, while their opponents have more than doubled, to 40 percent.

Of course, politicians of all stripes are not faring well among the public these days. But in data we have recently collected, the Tea Party ranks lower than any of the 23 other groups we asked about — lower than both Republicans and Democrats. It is even less popular than much maligned groups like “atheists” and “Muslims.” Interestingly, one group that approaches it in unpopularity is the Christian Right.

The strange thing is that over the last five years, Americans have moved in an economically conservative direction: they are more likely to favor smaller government, to oppose redistribution of income and to favor private charities over government to aid the poor. While none of these opinions are held by a majority of Americans, the trends would seem to favor the Tea Party. So why are its negatives so high? To find out, we need to examine what kinds of people actually support it.

Beginning in 2006 we interviewed a representative sample of 3,000 Americans as part of our continuing research into national political attitudes, and we returned to interview many of the same people again this summer. As a result, we can look at what people told us, long before there was a Tea Party, to predict who would become a Tea Party supporter five years later. We can also account for multiple influences simultaneously — isolating the impact of one factor while holding others constant.

Our analysis casts doubt on the Tea Party’s “origin story.” Early on, Tea Partiers were often described as nonpartisan political neophytes. Actually, the Tea Party’s supporters today were highly partisan Republicans long before the Tea Party was born, and were more likely than others to have contacted government officials. In fact, past Republican affiliation is the single strongest predictor of Tea Party support today.

What’s more, contrary to some accounts, the Tea Party is not a creature of the Great Recession. Many Americans have suffered in the last four years, but they are no more likely than anyone else to support the Tea Party. And while the public image of the Tea Party focuses on a desire to shrink government, concern over big government is hardly the only or even the most important predictor of Tea Party support among voters.

So what do Tea Partiers have in common? They are overwhelmingly white, but even compared to other white Republicans, they had a low regard for immigrants and blacks long before Barack Obama was president, and they still do.

More important, they were disproportionately social conservatives in 2006 — opposing abortion, for example — and still are today. Next to being a Republican, the strongest predictor of being a Tea Party supporter today was a desire, back in 2006, to see religion play a prominent role in politics. And Tea Partiers continue to hold these views: they seek “deeply religious” elected officials, approve of religious leaders’ engaging in politics and want religion brought into political debates. The Tea Party’s generals may say their overriding concern is a smaller government, but not their rank and file, who are more concerned about putting God in government.

This inclination among the Tea Party faithful to mix religion and politics explains their support for Representative Michele Bachmann of Minnesota and Gov. Rick Perry of Texas. Their appeal to Tea Partiers lies less in what they say about the budget or taxes, and more in their overt use of religious language and imagery, including Mrs. Bachmann’s lengthy prayers at campaign stops and Mr. Perry’s prayer rally in Houston.

Yet it is precisely this infusion of religion into politics that most Americans increasingly oppose. While over the last five years Americans have become slightly more conservative economically, they have swung even further in opposition to mingling religion and politics. It thus makes sense that the Tea Party ranks alongside the Christian Right in unpopularity.

On everything but the size of government, Tea Party supporters are increasingly out of step with most Americans, even many Republicans. Indeed, at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum, today’s Tea Party parallels the anti-Vietnam War movement which rallied behind George S. McGovern in 1972. The McGovernite activists brought energy, but also stridency, to the Democratic Party — repelling moderate voters and damaging the Democratic brand for a generation. By embracing the Tea Party, Republicans risk repeating history.

David E. Campbell, an associate professor of political science at Notre Dame, and Robert D. Putnam, a professor of public policy at Harvard, are the authors of “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us.”

Thursday, August 25, 2011

World of Class Warfare - The Poor's Free Ride Is Over

This is a classic from Jon Stewart -- Air Date August 18, 2011. A must-see!

http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/thu-august-18-2011/world-of-class-warfare---the-poor-s-free-ride-is-over

http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/thu-august-18-2011/world-of-class-warfare---the-poor-s-free-ride-is-over

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Interesting Interview with Ken Rogoff and Paul Krugman

From Fareed Zakaria's GPS show on CNN -- air date August 14, 2011:

http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1108/14/fzgps.01.html

ZAKARIA: Joining me now to talk about Wall Street's wild week, what it means or doesn't mean, and what may lay behind it and what lays - lies ahead of us, two of the world's top economists.

Paul Krugman won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economics, and he is a columnist for "The New York Times." Kenneth Rogoff is a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, now a professor of economics at Harvard University. Welcome to you both.

Paul, let me start with you. The one thing we saw over the week was markets up, markets down, but the one trend that seemed persistent was there is a great demand for U.S. treasuries despite the fact that the S&P downgraded it.

You've been talking a lot about this. Explain in your view what does it mean that in moments like this U.S. treasuries are still in demand and what that does is push interest rates even lower than they are.

PAUL KRUGMAN, COLUMNIST, NEW YORK TIMES: Well, what it tells you is that the investors, the market, are not at all afraid of what the - if you like, the policy elite or people like Standard & Poor's are telling them they should be afraid of.

You know, we - we've got all of Washington, all of Brussels, all of Frankfurt saying debt deficits, this is the big problem. And what we actually have in reality is markets are terrified of prolonged stagnation, maybe another recession. They still see government debt as - U.S. government debt, at any rate - as the safest thing out there, and are saying, if - if this was a reaction of the S&P downgrade, it was the market's saying, you know, we're afraid that that downgrade is going to lead to even more contractionary policy, more austerity, pushing us deeper into the hole.

So it's - it's a - you know, it's a reality test, right? So we just - just had a wake-up call that said, hey, you guys have been worrying about the entirely wrong things. The really scary thing here is the prospect of what amounts to a - a somewhat reduced version of the Great Depression in - in the Western world.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff, worrying about the wrong thing?

KEN ROGOFF, FORMER CHIEF ECONOMIST, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND: Well, I think the downgrade was well justified. It's a very volatile world. And the reason there's still a demand for treasuries is they've been downgraded a little bit to AA plus. That looks pretty good compared to a lot of the other options right now.

It's a very, very difficult time for investors. There is a financial panic going on at some level. Some of it's adjusting to a lower growth expectations, maybe a third of what we're seeing. Two- thirds of it is the idea no one's home - not in Europe, not in the United States. There's no leadership. And I really think that's what's driving the panic.

ZAKARIA: But you wrote in an article of yours that you think that this is part of actually a broader phenomenon which is that people are realizing this is not a classic recession, this is not a classic cyclical downturn. This is what you call a great contraction. Explain what you mean by that.

ROGOFF: Well, recessions we have periodically since World War II, but we haven't really had a financial crisis as we're having now. And Carmen Reinhart and I think of this as a great contraction, the second one, the first being the Great Depression, where it's not just unemployment, it's not just output, but it's also credit, housing and a lot of other things which are contracting. These things last much longer because of the debt overhang that we started with. After a typical recession, you come galloping out. Six months after it ended, you're back to where you started. Another six or 12 months, you're back to trend.

If you look at a contraction, one of these post-financial crisis events, it can take up to four or five years just to get back to where you started. So people are talking about a double dip, a second recession. We never left the first one.

ZAKARIA: So, Paul Krugman, what the implication of what Ken Rogoff is saying is spending large amounts of money on stimulus programs is not going to be the answer because, until the debt overhang works its way off, you're not going to get back to trend growth. So, in that circumstance, you'll be wasting the money. Is that - is -

KRUGMAN: No, that's not at all what it implies. At least not - not - I think my analytical framework, the way I think about this, is not very different from Ken's. At least I certainly believed from day one of this slump that it was going to be something very different from one of your standard V-shaped, you know, down and up recessions, that it was going to last a long time.

One of the things we can do, at least a partial answer, is in fact to have institutions that are able to issue debt - namely the government - do so and sustain spending and, among other things, by maintaining employment, by maintaining income, you make it easier for the private sector to work down that overhang of debt.

ZAKARIA: Ken, are you in favor of a - a second or a significant additional stimulus in the way that I think Paul Krugman is?

ROGOFF: No. I - I think that's where we part ways on this. I mean, I think that creates a - a debt overhang in the terms of future taxes that is not a magic bullet because it's not a typical recession. I do think, if we used our credit to help facilitate one of these plans to bring down the mortgage debt in this targeted way, and it could involve a significant amount, that I would definitely consider. I mean, that's how - that's how I would do it.

Now, obviously, you know, things go from bad to worse, then you start taking out more and more things from the tool kit, but I would start with targeting the mortgages, then higher inflation, try to do some structural reforms and, of course, you know, if things are still going badly, I'm open to more ideas.

ZAKARIA: Paul -

KRUGMAN: Can I just break in?

ZAKARIA: Yes. Yes.

KRUGMAN: I would say things - things have already gone from bad to worse. I mean, this is a terrible, terrible situation out there. You know, we - we talk about it, we look at GDP, whatever. We have nine percent unemployment and, more to the point, we have long-term unemployment at levels not seen since the Great Depression. Just an incredible - incredibly large number of people trapped in basically permanent unemployment.

This is something that desperately needs addressing. And I would be saying we should not be trying one tool after another from the tool kit a little bit at a time. At this point, we really want to be throwing everything we can get mobilized at it.

I - I don't - I don't think fiscal stimulus is - is a magic bullet. I'm not sure that inflation is a magic bullet in the sense that it's kind of hard to get, unless you're doing a bunch of other things. So we - we should be trying all of these things.

And, you know, what - how did the Great Depression end? How did - how did that end? It ended, actually, of course, with World War II, but that - which was a massive fiscal expansion, but also involved a substantial amount of inflation, which eroded the debt. What we need - hopefully we don't need a world war to get there, but we need - we need this kind of all-out effort which we're not going to get (ph) -

ZAKARIA: We're going to have to take a break. When we come back, we'll ask what exactly should the worries about the deficit be? Is - is that something to be taken seriously at all? When we come back.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

ZAKARIA: And we are back with Paul Krugman and Paul Rogoff, talking about the economy, the markets and everything else.

Paul Krugman, before we took a break, you talked about the solution to getting us out of this crisis, and you compared it to the '30s and pointed out that World War II got us out of the Depression. This was a massive stimulus, massive fiscal expansion. But aren't we in a different world?

We are, right now, the United States, at 10 percent of budget - budget deficit, 10 percent of GDP, which is the second highest in the industrial world. In two years we'll - our debt-to-GDP ratio goes to 100 percent. That strikes me as a situation which there's got to - presumably there is some upper limit. You can't just keep spending money and incur these larger and larger debt loads.

KRUGMAN: Oh, I don't get us to - I think those numbers are a bit high, about the - about the deficit, a couple - the debt levels a couple years out. It takes longer than that.

But the main thing to say is, look, think about the costs versus benefits right now. Basically, the U.S. government can borrow money and repay in constant dollars less than it borrowed. Are we really saying that there are no projects that the federal government can undertake that have an even slightly positive rate of return? Especially when you bear in mind that many of the workers and resources that you employ on those projects would be otherwise be unemployed.

The world wants to buy U.S. bonds. Let's - let's supply some more, and let's use those bonds to do something useful which might, among other things, help to get us out of this terrible, terrible slump.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff?

ROGOFF: Well, I think you have to be careful about assuming that these low interest rates are going to last indefinitely. They were very low for subprime mortgage borrowers a few years ago. Interest rates can turn like the weather.

But I - I also question how much just untargeted stimulus would really work. Infrastructure spending, if well spent, that's great. I'm all for that. I'd borrow for that, assuming we're not paying Boston Big Dig kind of prices for the infrastructure.

ZAKARIA: But, even if you were, wouldn't John Maynard Keynes say that if you could employ people to dig a ditch and then fill it up again, that's fine. They're being productively employed, they pay taxes, so maybe the big - maybe Boston's Big Dig was - was just fine after all?

KRUGMAN: Think about World War II, right? That was not - that was actually negative for social product spending, and yet it brought us out. I mean, partly because you want to put these things together, if we say, look, we could use some inflation. Ken and I are both saying that, which is of course anathema to a lot of people in - in Washington, but is in fact what the basic logic says.

It's very hard to get inflation in a depressed economy. But if you have a program of government spending plus an expansionary policy by the Fed, you could get that. So if you think about using all of these things together, you could accomplish, you know, a great deal.

I mean, if we - if we discovered that, you know, space aliens were planning to attack and we needed a - a massive buildup to counter the - the space alien threat, and really inflation and budget deficits took secondary place to that, this slump would be over in 18 months. And then if we discovered, oops, we made a mistake there aren't actually any space aliens -

(CROSSTALK)

ROGOFF: So we need Orson Wells is what you're say?

KRUGMAN: No. That's a - that's a - there was a "Twilight Zone" episode like this, which scientists fake an alien threat in order to achieve world peace. Well, this time we don't need it - we need it in order to get some fiscal stimulus.

But, no. I mean, the point is -

ZAKARIA: But Ken - but Ken wouldn't agree with that, right? The space aliens wouldn't work -

ROGOFF: It's not so clear that -

ZAKARIA: Go ahead (ph).

ROGOFF: I think it's not so clear that Keynes was right. I mean, there have been decades and decades of debate about that, about whether digging ditches is such a good idea. And my read of the debate is when the government does really useful things and spends the money in useful ways, it's a good idea. But when it just dig ditches and fills them in, it's not productive and leaves you with debt.

I don't - I don't think that's such a no-brainer. There are people going around saying, oh, Keynes was right. Everything Keynes said was right. I think this is a different animal, with this debt overhang that you need to think about from the standard Keynesian framework.

KRUGMAN: I - I guess I just don't agree. I mean, I think the - the debt overhang - but that was an issue in the '30s, too, private sector debt overhang. We came into this with higher public debt than I would have liked, right? We're really, in some ways, paying the cost to the Bush tax cuts and the Bush unfunded wars, which leave us with a - a higher starting point of debt.

But - but, you know, the - the thing that drives me crazy about this debate, if I can say, is that we have these hypothetical risks. All those hypothetical things are leaving us doing nothing about the actual thing that's happening, which is mass unemployment, mass waste of human resources, mass waste of - of physical resources.

This is - you know, what's happening is we - we are hemorrhaging economic possibilities and also destroying a lot of lives by letting this thing drift on. And we're inventing these - you know, sometimes ghosts are real, I guess, but we're inventing these phantom threats to keep us from - from acting.

ZAKARIA: Do you - do you think that the lesson from history, Ken, in terms of these kind of great contractions - because other countries have had - we - we have not had something like this since the 1930s, but there have been other examples. It tells you that until you get these debt levels down, no matter what the government does, it's not going to get you back to robust growth?

ROGOFF: I do, because what happens as you're growing slowly, the debt problems start blowing up on you. That's happening very dramatically in Europe. They had a - a philosophy and approach of things are going to get much better. this is an ordinary but big recession. If we can just hang on, we're going to grow really fast, the debt problems will go away.

Well, guess what? They're not growing fast enough. The debt problems are - are imploding. That's slowing growth, and it's a self- feeding cycle.

KRUGMAN: I guess I'm - I'm a little puzzled here because, again, the thing that's holding us back right now in the United States, although there are - there are those peripheral European countries that are having a - a very different kind of problem, partly because they don't have their own currencies.

But, in the United States, what's holding us back is private sector debt. And, yes, we - we're not going to have a self sustaining recovery unless that private sector debt could be brought down (ph).

ZAKARIA: Just to be clear, Paul, what you mean by that is individuals have a lot of debt on their - on their balance sheets?

KRUGMAN: Yes. That's what's holding us back, and we do need to bring that down, at least bring it down relative to incomes. So what you need to do is you need to have policies to make incomes grow. You need - and that can include government spending, which is going to add to - to public debt, but it's going to reduce the burden of private debt. It can include inflationary policies, and it can include - and it include deliberate forgiveness.

The idea that - that this has all faded, that we cannot do anything to grow because we have to wait for some natural process to bring that - that debt down, that - that doesn't follow from the analysis. It's - it is the - there is a huge overhang of debt, which is the - at least as I see it, exactly the reason why we need very activist government policies.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff, the last word?

ROGOFF: I do think that the debt of the government, of course it's important. The social security, concerns over future medical spending. A lot of businesses are - and - and people who could invest, could hire people are worried of where the government's going, where taxes are going, what's going to happen to their savings. So I don't think -

KRUGMAN: There's not a hint of that in the data.

ROGOFF: I don't think it's such a - well, not a hint of that? People aren't hiring, and - and there - there's a lot of surveys and -

KRUGMAN: Because they can't sell.

ROGOFF: -- and such showing people (ph).

Yes, but I mean - I mean, interest rates are always low before a crisis. You can't necessarily say that that tells you it's not going to happen.

KRUGMAN: I'm - I guess I'm still in this position of saying that - that things that we have no evidence for, that are supposed to be dangerous, are being - you're blaming it - lots of people are blaming them for something which is - looks to me like straightforward there isn't enough spending in the economy. ROGOFF: We have - we have centuries of examples.

KRUGMAN: Not - I don't read that history the same way.

ZAKARIA: All right. We're going to have to leave it at that.

Paul Krugman, Ken Rogoff we'll have you back very soon to see which way the wind is blowing one of these weeks (ph). Thank you

http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/1108/14/fzgps.01.html

ZAKARIA: Joining me now to talk about Wall Street's wild week, what it means or doesn't mean, and what may lay behind it and what lays - lies ahead of us, two of the world's top economists.

Paul Krugman won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economics, and he is a columnist for "The New York Times." Kenneth Rogoff is a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, now a professor of economics at Harvard University. Welcome to you both.

Paul, let me start with you. The one thing we saw over the week was markets up, markets down, but the one trend that seemed persistent was there is a great demand for U.S. treasuries despite the fact that the S&P downgraded it.

You've been talking a lot about this. Explain in your view what does it mean that in moments like this U.S. treasuries are still in demand and what that does is push interest rates even lower than they are.

PAUL KRUGMAN, COLUMNIST, NEW YORK TIMES: Well, what it tells you is that the investors, the market, are not at all afraid of what the - if you like, the policy elite or people like Standard & Poor's are telling them they should be afraid of.

You know, we - we've got all of Washington, all of Brussels, all of Frankfurt saying debt deficits, this is the big problem. And what we actually have in reality is markets are terrified of prolonged stagnation, maybe another recession. They still see government debt as - U.S. government debt, at any rate - as the safest thing out there, and are saying, if - if this was a reaction of the S&P downgrade, it was the market's saying, you know, we're afraid that that downgrade is going to lead to even more contractionary policy, more austerity, pushing us deeper into the hole.

So it's - it's a - you know, it's a reality test, right? So we just - just had a wake-up call that said, hey, you guys have been worrying about the entirely wrong things. The really scary thing here is the prospect of what amounts to a - a somewhat reduced version of the Great Depression in - in the Western world.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff, worrying about the wrong thing?

KEN ROGOFF, FORMER CHIEF ECONOMIST, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND: Well, I think the downgrade was well justified. It's a very volatile world. And the reason there's still a demand for treasuries is they've been downgraded a little bit to AA plus. That looks pretty good compared to a lot of the other options right now.

It's a very, very difficult time for investors. There is a financial panic going on at some level. Some of it's adjusting to a lower growth expectations, maybe a third of what we're seeing. Two- thirds of it is the idea no one's home - not in Europe, not in the United States. There's no leadership. And I really think that's what's driving the panic.

ZAKARIA: But you wrote in an article of yours that you think that this is part of actually a broader phenomenon which is that people are realizing this is not a classic recession, this is not a classic cyclical downturn. This is what you call a great contraction. Explain what you mean by that.

ROGOFF: Well, recessions we have periodically since World War II, but we haven't really had a financial crisis as we're having now. And Carmen Reinhart and I think of this as a great contraction, the second one, the first being the Great Depression, where it's not just unemployment, it's not just output, but it's also credit, housing and a lot of other things which are contracting. These things last much longer because of the debt overhang that we started with. After a typical recession, you come galloping out. Six months after it ended, you're back to where you started. Another six or 12 months, you're back to trend.

If you look at a contraction, one of these post-financial crisis events, it can take up to four or five years just to get back to where you started. So people are talking about a double dip, a second recession. We never left the first one.

ZAKARIA: So, Paul Krugman, what the implication of what Ken Rogoff is saying is spending large amounts of money on stimulus programs is not going to be the answer because, until the debt overhang works its way off, you're not going to get back to trend growth. So, in that circumstance, you'll be wasting the money. Is that - is -

KRUGMAN: No, that's not at all what it implies. At least not - not - I think my analytical framework, the way I think about this, is not very different from Ken's. At least I certainly believed from day one of this slump that it was going to be something very different from one of your standard V-shaped, you know, down and up recessions, that it was going to last a long time.

One of the things we can do, at least a partial answer, is in fact to have institutions that are able to issue debt - namely the government - do so and sustain spending and, among other things, by maintaining employment, by maintaining income, you make it easier for the private sector to work down that overhang of debt.

ZAKARIA: Ken, are you in favor of a - a second or a significant additional stimulus in the way that I think Paul Krugman is?

ROGOFF: No. I - I think that's where we part ways on this. I mean, I think that creates a - a debt overhang in the terms of future taxes that is not a magic bullet because it's not a typical recession. I do think, if we used our credit to help facilitate one of these plans to bring down the mortgage debt in this targeted way, and it could involve a significant amount, that I would definitely consider. I mean, that's how - that's how I would do it.

Now, obviously, you know, things go from bad to worse, then you start taking out more and more things from the tool kit, but I would start with targeting the mortgages, then higher inflation, try to do some structural reforms and, of course, you know, if things are still going badly, I'm open to more ideas.

ZAKARIA: Paul -

KRUGMAN: Can I just break in?

ZAKARIA: Yes. Yes.

KRUGMAN: I would say things - things have already gone from bad to worse. I mean, this is a terrible, terrible situation out there. You know, we - we talk about it, we look at GDP, whatever. We have nine percent unemployment and, more to the point, we have long-term unemployment at levels not seen since the Great Depression. Just an incredible - incredibly large number of people trapped in basically permanent unemployment.

This is something that desperately needs addressing. And I would be saying we should not be trying one tool after another from the tool kit a little bit at a time. At this point, we really want to be throwing everything we can get mobilized at it.

I - I don't - I don't think fiscal stimulus is - is a magic bullet. I'm not sure that inflation is a magic bullet in the sense that it's kind of hard to get, unless you're doing a bunch of other things. So we - we should be trying all of these things.

And, you know, what - how did the Great Depression end? How did - how did that end? It ended, actually, of course, with World War II, but that - which was a massive fiscal expansion, but also involved a substantial amount of inflation, which eroded the debt. What we need - hopefully we don't need a world war to get there, but we need - we need this kind of all-out effort which we're not going to get (ph) -

ZAKARIA: We're going to have to take a break. When we come back, we'll ask what exactly should the worries about the deficit be? Is - is that something to be taken seriously at all? When we come back.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

ZAKARIA: And we are back with Paul Krugman and Paul Rogoff, talking about the economy, the markets and everything else.

Paul Krugman, before we took a break, you talked about the solution to getting us out of this crisis, and you compared it to the '30s and pointed out that World War II got us out of the Depression. This was a massive stimulus, massive fiscal expansion. But aren't we in a different world?

We are, right now, the United States, at 10 percent of budget - budget deficit, 10 percent of GDP, which is the second highest in the industrial world. In two years we'll - our debt-to-GDP ratio goes to 100 percent. That strikes me as a situation which there's got to - presumably there is some upper limit. You can't just keep spending money and incur these larger and larger debt loads.

KRUGMAN: Oh, I don't get us to - I think those numbers are a bit high, about the - about the deficit, a couple - the debt levels a couple years out. It takes longer than that.

But the main thing to say is, look, think about the costs versus benefits right now. Basically, the U.S. government can borrow money and repay in constant dollars less than it borrowed. Are we really saying that there are no projects that the federal government can undertake that have an even slightly positive rate of return? Especially when you bear in mind that many of the workers and resources that you employ on those projects would be otherwise be unemployed.

The world wants to buy U.S. bonds. Let's - let's supply some more, and let's use those bonds to do something useful which might, among other things, help to get us out of this terrible, terrible slump.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff?

ROGOFF: Well, I think you have to be careful about assuming that these low interest rates are going to last indefinitely. They were very low for subprime mortgage borrowers a few years ago. Interest rates can turn like the weather.

But I - I also question how much just untargeted stimulus would really work. Infrastructure spending, if well spent, that's great. I'm all for that. I'd borrow for that, assuming we're not paying Boston Big Dig kind of prices for the infrastructure.

ZAKARIA: But, even if you were, wouldn't John Maynard Keynes say that if you could employ people to dig a ditch and then fill it up again, that's fine. They're being productively employed, they pay taxes, so maybe the big - maybe Boston's Big Dig was - was just fine after all?

KRUGMAN: Think about World War II, right? That was not - that was actually negative for social product spending, and yet it brought us out. I mean, partly because you want to put these things together, if we say, look, we could use some inflation. Ken and I are both saying that, which is of course anathema to a lot of people in - in Washington, but is in fact what the basic logic says.

It's very hard to get inflation in a depressed economy. But if you have a program of government spending plus an expansionary policy by the Fed, you could get that. So if you think about using all of these things together, you could accomplish, you know, a great deal.

I mean, if we - if we discovered that, you know, space aliens were planning to attack and we needed a - a massive buildup to counter the - the space alien threat, and really inflation and budget deficits took secondary place to that, this slump would be over in 18 months. And then if we discovered, oops, we made a mistake there aren't actually any space aliens -

(CROSSTALK)

ROGOFF: So we need Orson Wells is what you're say?

KRUGMAN: No. That's a - that's a - there was a "Twilight Zone" episode like this, which scientists fake an alien threat in order to achieve world peace. Well, this time we don't need it - we need it in order to get some fiscal stimulus.

But, no. I mean, the point is -

ZAKARIA: But Ken - but Ken wouldn't agree with that, right? The space aliens wouldn't work -

ROGOFF: It's not so clear that -

ZAKARIA: Go ahead (ph).

ROGOFF: I think it's not so clear that Keynes was right. I mean, there have been decades and decades of debate about that, about whether digging ditches is such a good idea. And my read of the debate is when the government does really useful things and spends the money in useful ways, it's a good idea. But when it just dig ditches and fills them in, it's not productive and leaves you with debt.

I don't - I don't think that's such a no-brainer. There are people going around saying, oh, Keynes was right. Everything Keynes said was right. I think this is a different animal, with this debt overhang that you need to think about from the standard Keynesian framework.

KRUGMAN: I - I guess I just don't agree. I mean, I think the - the debt overhang - but that was an issue in the '30s, too, private sector debt overhang. We came into this with higher public debt than I would have liked, right? We're really, in some ways, paying the cost to the Bush tax cuts and the Bush unfunded wars, which leave us with a - a higher starting point of debt.

But - but, you know, the - the thing that drives me crazy about this debate, if I can say, is that we have these hypothetical risks. All those hypothetical things are leaving us doing nothing about the actual thing that's happening, which is mass unemployment, mass waste of human resources, mass waste of - of physical resources.

This is - you know, what's happening is we - we are hemorrhaging economic possibilities and also destroying a lot of lives by letting this thing drift on. And we're inventing these - you know, sometimes ghosts are real, I guess, but we're inventing these phantom threats to keep us from - from acting.

ZAKARIA: Do you - do you think that the lesson from history, Ken, in terms of these kind of great contractions - because other countries have had - we - we have not had something like this since the 1930s, but there have been other examples. It tells you that until you get these debt levels down, no matter what the government does, it's not going to get you back to robust growth?

ROGOFF: I do, because what happens as you're growing slowly, the debt problems start blowing up on you. That's happening very dramatically in Europe. They had a - a philosophy and approach of things are going to get much better. this is an ordinary but big recession. If we can just hang on, we're going to grow really fast, the debt problems will go away.

Well, guess what? They're not growing fast enough. The debt problems are - are imploding. That's slowing growth, and it's a self- feeding cycle.

KRUGMAN: I guess I'm - I'm a little puzzled here because, again, the thing that's holding us back right now in the United States, although there are - there are those peripheral European countries that are having a - a very different kind of problem, partly because they don't have their own currencies.

But, in the United States, what's holding us back is private sector debt. And, yes, we - we're not going to have a self sustaining recovery unless that private sector debt could be brought down (ph).

ZAKARIA: Just to be clear, Paul, what you mean by that is individuals have a lot of debt on their - on their balance sheets?

KRUGMAN: Yes. That's what's holding us back, and we do need to bring that down, at least bring it down relative to incomes. So what you need to do is you need to have policies to make incomes grow. You need - and that can include government spending, which is going to add to - to public debt, but it's going to reduce the burden of private debt. It can include inflationary policies, and it can include - and it include deliberate forgiveness.

The idea that - that this has all faded, that we cannot do anything to grow because we have to wait for some natural process to bring that - that debt down, that - that doesn't follow from the analysis. It's - it is the - there is a huge overhang of debt, which is the - at least as I see it, exactly the reason why we need very activist government policies.

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff, the last word?

ROGOFF: I do think that the debt of the government, of course it's important. The social security, concerns over future medical spending. A lot of businesses are - and - and people who could invest, could hire people are worried of where the government's going, where taxes are going, what's going to happen to their savings. So I don't think -

KRUGMAN: There's not a hint of that in the data.

ROGOFF: I don't think it's such a - well, not a hint of that? People aren't hiring, and - and there - there's a lot of surveys and -

KRUGMAN: Because they can't sell.

ROGOFF: -- and such showing people (ph).

Yes, but I mean - I mean, interest rates are always low before a crisis. You can't necessarily say that that tells you it's not going to happen.

KRUGMAN: I'm - I guess I'm still in this position of saying that - that things that we have no evidence for, that are supposed to be dangerous, are being - you're blaming it - lots of people are blaming them for something which is - looks to me like straightforward there isn't enough spending in the economy. ROGOFF: We have - we have centuries of examples.

KRUGMAN: Not - I don't read that history the same way.

ZAKARIA: All right. We're going to have to leave it at that.

Paul Krugman, Ken Rogoff we'll have you back very soon to see which way the wind is blowing one of these weeks (ph). Thank you

Why are Republicans so Upset About Poor People's Taxes?

From Ezra Klein -- why are Republicans so upset about poor people's taxes:

Democrats are making Americans angry with poll-tested language arguing that the rich don't pay enough, so Republicans are responding with an argument that the poor are mooching off the middle class. Then there's the underlying ideological framework: Republicans believe, either implicitly or explicitly, that the economy is really driven by well-compensated, wildly productive geniuses at the top, and so the true aim of tax policy is keeping their tax burden low so they have sufficient encouragement to unleash their potential. Democrats believe those folks have so much money that they're no longer primarily driven by monetary concerns and that, either way, the key question for the economy is how to get more demand into it quickly, and for that, tax cuts to the poor are clearly superior, as the poor spend the money they get.

Link is here: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/?wpisrc=nl_wonk

Democrats are making Americans angry with poll-tested language arguing that the rich don't pay enough, so Republicans are responding with an argument that the poor are mooching off the middle class. Then there's the underlying ideological framework: Republicans believe, either implicitly or explicitly, that the economy is really driven by well-compensated, wildly productive geniuses at the top, and so the true aim of tax policy is keeping their tax burden low so they have sufficient encouragement to unleash their potential. Democrats believe those folks have so much money that they're no longer primarily driven by monetary concerns and that, either way, the key question for the economy is how to get more demand into it quickly, and for that, tax cuts to the poor are clearly superior, as the poor spend the money they get.

Link is here: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/?wpisrc=nl_wonk

Stop Coddling the Super Rich

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/15/opinion/stop-coddling-the-super-rich.html

From Warren Buffett --

While the poor and middle class fight for us in Afghanistan, and while most Americans struggle to make ends meet, we mega-rich continue to get our extraordinary tax breaks.

From Warren Buffett --

While the poor and middle class fight for us in Afghanistan, and while most Americans struggle to make ends meet, we mega-rich continue to get our extraordinary tax breaks.

Why Lower Income Americans Pay No Income Tax

This paper offers a rational analysis of why lower income Americans pay no income tax:

1001547-Why-No-Income-Tax.pdf (application/pdf Object)

And here's another report from Citizens for Tax Justice:

http://www.ctj.org/pdf/taxday2010.pdf

1001547-Why-No-Income-Tax.pdf (application/pdf Object)

And here's another report from Citizens for Tax Justice:

http://www.ctj.org/pdf/taxday2010.pdf

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Saturday, June 4, 2011

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Sunday, May 29, 2011

How Ignorant Are Americans?

This article from Newsweek (link below) gets at the crux of the matter. Most Americans are uninformed about their government (i.e. ignorant), and they generally make no effort to become informed despite this being more possible than ever because of the Internet. This is how we get fooled by slogans, by fear-mongering, and by outright falsehoods. No one takes the time to investigate. There is no excuse for this -- average Americans can do much better.

http://www.newsweek.com/2011/03/20/how-dumb-are-we.html

http://www.newsweek.com/2011/03/20/how-dumb-are-we.html

Saturday, May 28, 2011

The GOP’s jobs agenda: Now more than ever - Ezra Klein

What is "now-more-than-everism" --

"“Here’s how it works,” Autor wrote in am e-mail. “1. You have a set of policies that you favor at all times and under all circumstances, e.g., cut taxes, remove regulations, drill-baby-drill, etc. 2. You see a problem that needs fixing (e.g., the economy stinks). 3. You say, ‘We need to enact my favored policies now more than ever.’ I believe that every item in the GOP list that you sent derives from this three step procedure."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/the-gops-jobs-agenda-now-more-than-ever/2011/05/19/AGqX7CCH_blog.html?wpisrc=nl_wonk

Quoting from Ezra in the article -- he really nails it:

"The best evidence that Washington has forgotten about the jobs crisis is to look at the plans emerging to address it. Yesterday's House GOP plan was a perfect example. It was, as MIT economist David Autor told me, a classic case of "now-more-than-everism": Everything on the agenda was also on the GOP's agenda in 2006, in 2002, in 1987, etc. It's lower taxes, less spending, fewer regulations, more trade agreements, more domestic oil production. You can argue about whether these proposals are good for the economy. But as Autor says, there's "no original thinking here directed at addressing the employment problem."

But that's because the document doesn't admit the existence of a particular unemployment crisis that might require a tailored response. The only problem it admits is, well, Democrats. “For the past four years, Democrats in Washington have enacted policies that undermine these basic concepts which have historically placed America at the forefront of the global marketplace," the document explains on its first page. "As a result, most Americans know someone who has recently lost a job, and small businesses and entrepreneurs lack the confidence needed to invest in our economy. Not since the Great Depression has our nation’s unemployment rate been this high this long.”

You don't have to admire the Democratic policy agenda to wonder if someone in Speaker Boehner's office shouldn't have raised his hand and pointed out that George W. Bush was president four years ago and he was a Republican, and perhaps there should be a pro forma mention of Wall Street and the financial crisis somewhere in this narrative. Sadly, the most significant employment crisis in generations has stopped generating new thinking and has become simply another opportunity to bash the other party while pushing your perennial agenda. That's a shame, because with 15 million unemployed and the recovery sputtering slight, we really do need new thinking and a sense of urgency on behalf of both the unemployed and the economy. In fact, we need it now more than ever. "

"“Here’s how it works,” Autor wrote in am e-mail. “1. You have a set of policies that you favor at all times and under all circumstances, e.g., cut taxes, remove regulations, drill-baby-drill, etc. 2. You see a problem that needs fixing (e.g., the economy stinks). 3. You say, ‘We need to enact my favored policies now more than ever.’ I believe that every item in the GOP list that you sent derives from this three step procedure."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/the-gops-jobs-agenda-now-more-than-ever/2011/05/19/AGqX7CCH_blog.html?wpisrc=nl_wonk

Quoting from Ezra in the article -- he really nails it:

"The best evidence that Washington has forgotten about the jobs crisis is to look at the plans emerging to address it. Yesterday's House GOP plan was a perfect example. It was, as MIT economist David Autor told me, a classic case of "now-more-than-everism": Everything on the agenda was also on the GOP's agenda in 2006, in 2002, in 1987, etc. It's lower taxes, less spending, fewer regulations, more trade agreements, more domestic oil production. You can argue about whether these proposals are good for the economy. But as Autor says, there's "no original thinking here directed at addressing the employment problem."

But that's because the document doesn't admit the existence of a particular unemployment crisis that might require a tailored response. The only problem it admits is, well, Democrats. “For the past four years, Democrats in Washington have enacted policies that undermine these basic concepts which have historically placed America at the forefront of the global marketplace," the document explains on its first page. "As a result, most Americans know someone who has recently lost a job, and small businesses and entrepreneurs lack the confidence needed to invest in our economy. Not since the Great Depression has our nation’s unemployment rate been this high this long.”